Breastfeeding vs. Formula Costs: Don’t Forget Women’s Time

This post may contains affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. Read the full disclosure here.

Before I was even pregnant, I spent a lot of time reading research papers and articles about breastfeeding vs. formula feeding. Formula feeding felt like the right decision for me but I wanted to make sure I hadn’t overlooked something in the current research.

Being frugal-focused, I also spent time looking into the financial implications of deciding on formula vs. breastfeeding.

All told, I spent a lot of time in the weeds of the breastfeeding and formula feeding literature. And I noticed one glaring, troubling trend in most of the pieces:

Acknowledgement of women’s time and physical sacrifice was severely lacking in breastfeeding vs. formula feeding comparisons.

The occasional article would make passing reference to women shouldering the feedings when breastfeeding. Or mention that breastfeeding isn’t free if you count women’s time.

However, the articles didn’t try to quantify how much time women spend feeding their babies, or – more importantly – the value of that time in lost earning potential or lost free time. As is so often the case, women’s work felt unseen. These articles also often miss feeding-related work such as lactation consultations and pumping.

Sharing this time burden was one of the reasons I did decide to exclusively formula feed. It is what I’ve always wanted, but breastfeeding ultimately wouldn’t have been in the cards for me either way. After having hyperemesis gravidarum all pregnancy, my body was just too depleted.

Even as a formula feeder who shares the feeding load pretty evenly my partner, I still feel like I am constantly feeding my baby. How are we not shouting from the rooftops about the time and energy doled out by breastfeeding moms?

We initially fed our kid about every 2-3 hours and each feed took about 45 minutes (burping is slower than you’d think). We no longer do night feeds but spend extra time during the day on solid food meals. About 5-6 hours of our time goes to feeding each day.

To help fill in the gap about the time, energy and money that goes into feeding a baby, I reached out to my online due-date group to learn more about their breastfeeding and formula-feeding experiences through a brief survey.

On average, families spent a whooping 786 hours feeding their babies in the first six months of life.

Below I break down the costs of feeding a baby, including time and money expenditures. Looking just for the summary highlights? Skip ahead to the ‘Totaling Up Breastfeeding vs. Formula Feeding Time and Costs‘ section.

Survey overview

I surveyed 123 recent parents to help answer the question: How much time, energy and money do parents spend feeding their infants during the first six months of life?

My online due date group is made up of new parents who had a baby in fall 2019. At the time of the survey, most babies in this group ranged in age from five months to seven months. There was one set of twins in the respondents.

Of the respondents, 52% exclusively fed their baby breastmilk since birth (including pumping and donor milk). An additional 40% fed a combination of breastmilk and formula. Eight percent were exclusively formula feeders (I’m not included in the data but I’d fall in this category).

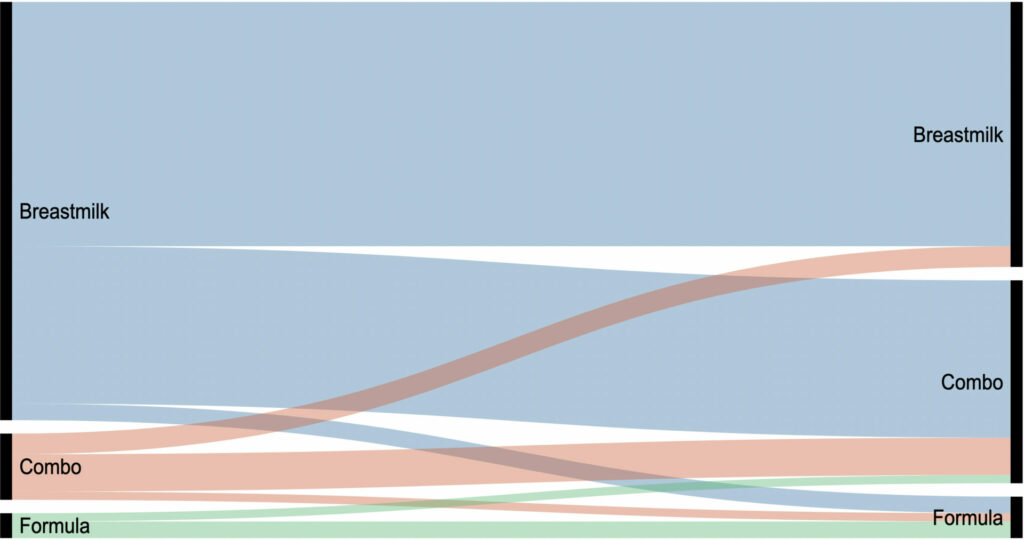

I also asked how they planned to feed their baby prior to birth to see to what extent families’ feeding plans change in the first six months of life. In the graphic below, you can see how the parents intended to feed their baby prior to birth (shown on the left), and where they ultimately ended up on feeding (on the right).

The majority of those who planned to feed their baby breastmilk did end up feeding breastmilk, either exclusively or in combination with formula.

Of the 123 respondents, six intended to formula feed from the beginning, two of whom opted to combo feed after birth. Only a handful of families (n=6) who originally planned for breastmilk or combo feeding switched exclusively to formula.

Of note here, the combo feeding category does include some families who only used a small amount of formula supplementation in the beginning while getting the hang of breastfeeding.

Thirteen families used donor breastmilk at some point in their feeding journeys. They spent about 1-2 hours acquiring donor breastmilk a week when using it. Nearly all of them did not incur a noticeable charge for donor milk as it was either covered by insurance or aggregated with other hospital charges. Donor breastmilk users are included in breastmilk feeding tallies.

Some methodological notes: This survey was done with convenience sampling so there is very likely sampling bias, and the results are not generalizable. If, for example, someone who struggled with breastfeeding was less likely to complete the survey, the results would underestimate feeding times and challenges.

“Were it not for the pandemic, I would have spent significantly more time pumping in months five and six”

Further, this survey was conducted during COVID-19 social distancing, so many working parents were at home. This likely leads to an underestimation of time spent pumping compared to normal circumstances.

Finally expenses reported were assumed to be in USD (there was a technical issue with a few questions that did not allow currency specification); those given in different currencies were converted using the current conversion rate.

Breastfeeding Vs. formula feeding: what do people say about their choice?

In a lot of spaces, breastfeeding vs. formula feeding is a very charged — and consequently difficult — topic for new parents. No matter what you decide, someone is waiting to tell why you are wrong and not doing the best for your baby.

A big motivator for my deep dive into the breastfeeding vs. formula literature was my fear that I’d have to defend my formula decision at every turn. I went into labor — women’s studies degree and the only breastfeeding randomized control study in my pocket — ready for battle.

Luckily, I only had to contend with one lactation consultant who said things that weren’t scientifically-backed, but who otherwise was polite and quick.

This article is not intended to take any stance on which whether breastfeeding vs. formula method is preferable. Fed is best. The responses of those in the survey also reflected how personal a decision breastfeeding vs. formula feeding is.

Here are just some examples of what parents said about their feeding experiences:

“[Breastfeeding] has been so convenient and I love feeding him from the breast!“

“Thank goodness for formula – it saved my baby’s life.”

“Really enjoy the bonding experience [of breastfeeding], even though it can be emotionally draining and definitely limits my freedom in this season of life.”

“[Formula] helped my baby thrive, even if it wasn’t what I hoped for or planned.“

“Breastfeeding is the hardest thing I’ve ever done, physically and mentally. I’m proud of myself for sticking it out to the point that we finally managed to make it work, and I would still breastfeed future children, but I wish it was more widely known how difficult it can be.”

Who feeds the baby?

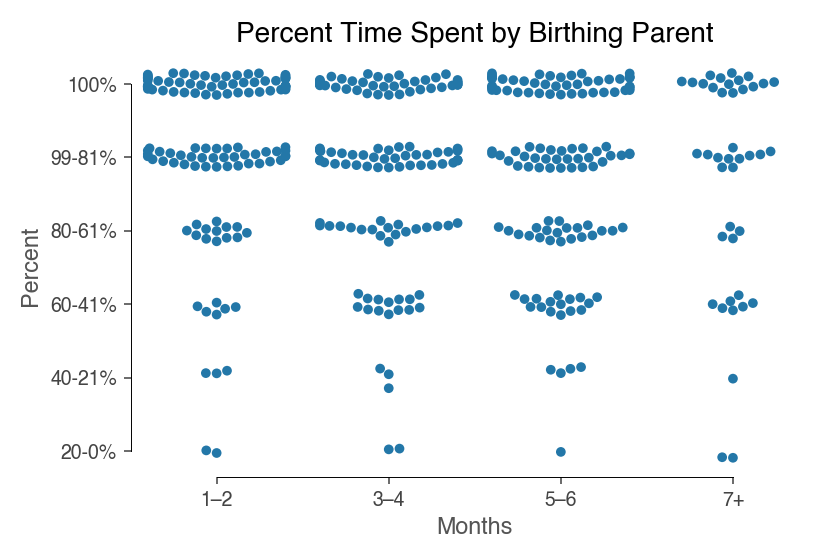

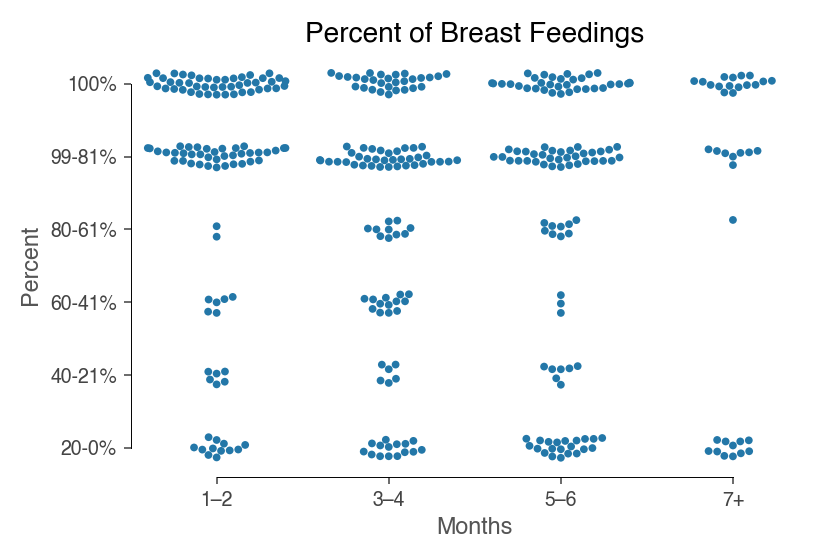

To gauge how often birth mothers are responsible for feeding their baby, respondents were asked to estimate the percentage of feedings done by the birthing parent (reported in two month increments).

Half of the families (n=61) reported the birthing parent was responsible for 100% of the feedings in the first and second month of their babies’ lives. An additional 30% (n=38) had the birthing parent feeding at least 80% of the time.

In months three and four of life, about 70% of families (n=85) still had the birthing parent doing at least 80% of the feedings. This number held fairly steady into months five and six as well (n=80). Note that the 7 month category has fewer responses, as the children ranged in age from 5-7 months.

For those feeding their babies directly from the breast, it makes sense that the birth parent would be the only one doing feeds. However, even among those who never fed directly from the breast (n=13), the birthing parent was more likely to feed the baby.

Those feeding not from the breast still reported the birth parent being responsible for feedings 75% of the time, on average, in the first two months of life. They did an average of 69% and 66% of the feedings in months 3-4 and 5-6, respectively.

This distribution of labor may reflect parental leave policies. Birthing parents are more likely to be on leave for physical recovery than non-birthing parents. Being the parent at home would make birthing parents the de facto feeder, regardless of whether they are breastfeeding vs. formula feeding.

Nevertheless, these responses suggest that the work and time required to feed a child is being shouldered by the birthing mother a majority of the time.

How much time is spent feeding a baby?

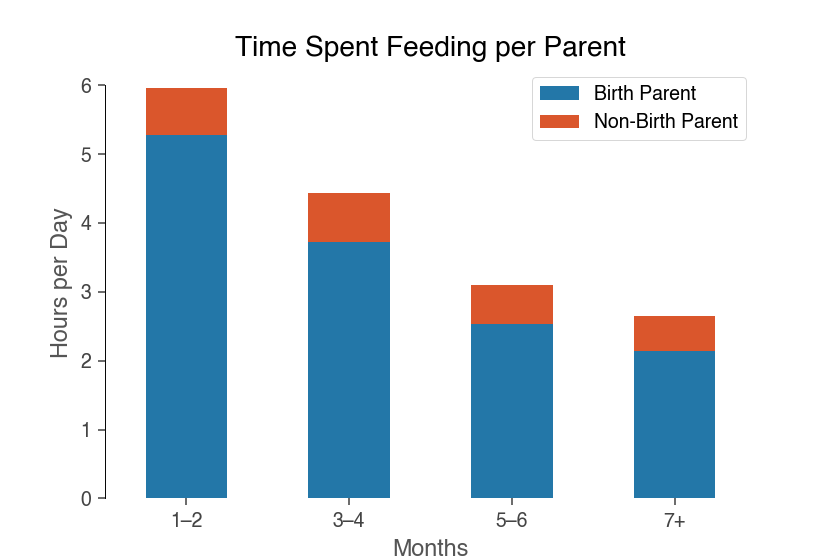

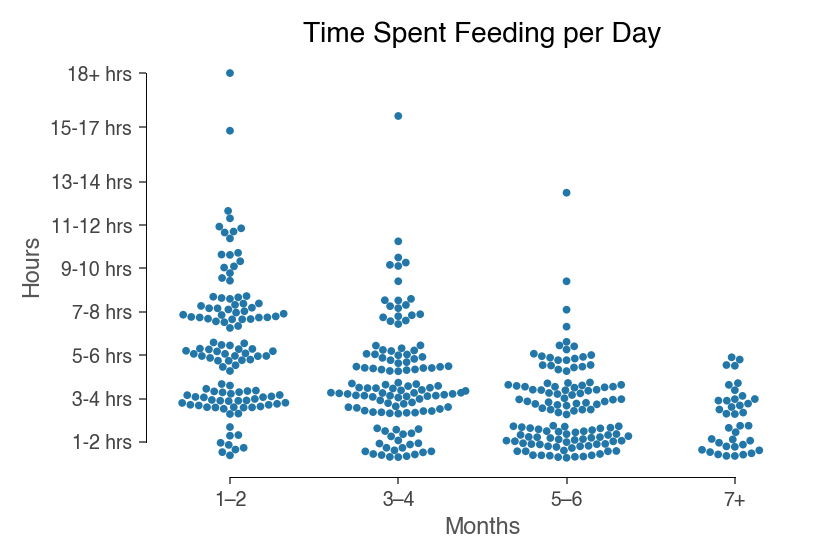

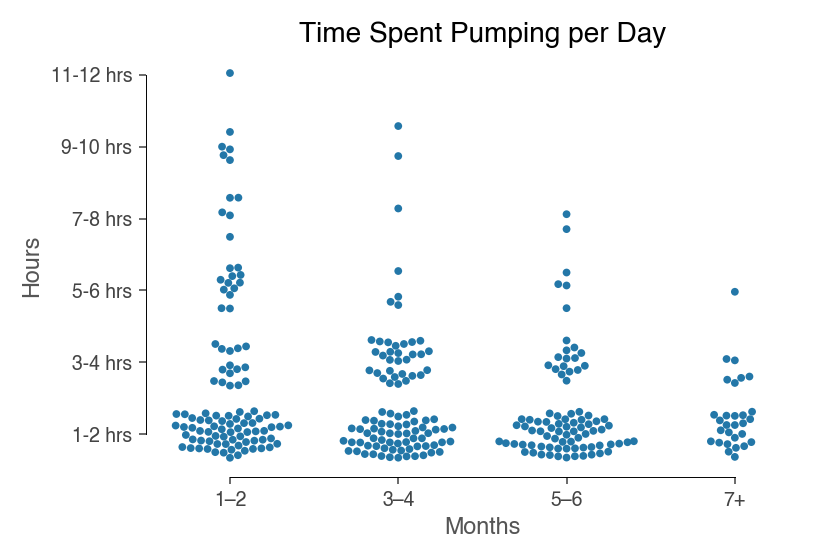

So how much time does it take to actually feed a baby? The graphic below shows how the hours spent feeding each day shifts over a baby’s first six months of life for the surveyed families:

In the first two months, respondents spent an average of 5.8 hours a day feeding their baby. In months three and four, babies were fed 4.3 hours a day; months five and six saw feeding times averaging 3 hours a day.

In looking at the plot above, you can see how many hours each respondent spent on feeding. In the first two months of life, 40% of people were feeding their babies an impressive seven or more hours a day – that’s a third or more of their 24-hour day.

“[Breastfeeding] is “unseen” work that most mothers are encouraged to do without question. My husband seems unaware that I have spent several hours per day breastfeeding every day for the past 6+ months. For most of us who are busy, working adults, several hours a day is all of our available free time.“

The average respondent spent approximately 348 hours feeding their baby in the first two months of life. They spent an additional 258 hours in months three and four, and 180 hours in months five and six.

“When people tell you you’ll spend your whole maternity leave feeding the baby, they’re not kidding.”

To put a dollar value on that time, let’s calculate the opportunity cost using average salary data from past US census data. The average 25-34 year old woman in the US makes $37,804 annually – roughly $18/hour.

If you paid our average respondent this hourly wage for her hours worked feeding a baby, it would cost $6264 for the first two months of life.

“As a freelancer, I stop work every few hours to breastfeed, and it really eats into my billable work hours.”

In months three and four the wages would total $4644 and months five and six would be an additional $3240.

Based on this napkin math, our average respondent had an opportunity cost of $14,148 to feed their baby in the first six months of life.

The vast majority of feedings in the sampled families were done directly from the breast. These means that the birthing mother shouldered this feeding work alone.

“Breastfeeding is a great time for me to multitask in pleasurable ways; I can’t work while nursing, but I can check social media or read. This factors a lot into my perception of the time spent breastfeeding.”

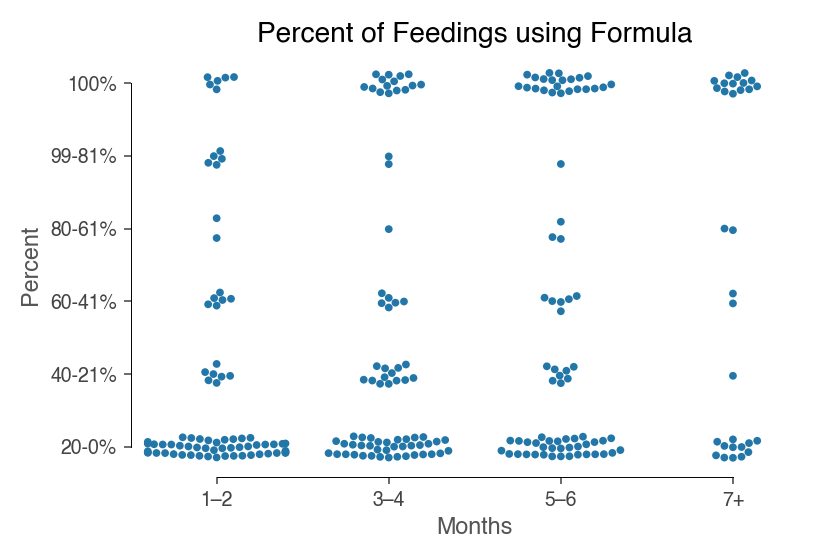

With formula feeding, you could theoretically spread this opportunity cost across both parents since the birthing parent is not required for breastmilk. That said, formula still represented a minority of feedings for the surveyed families:

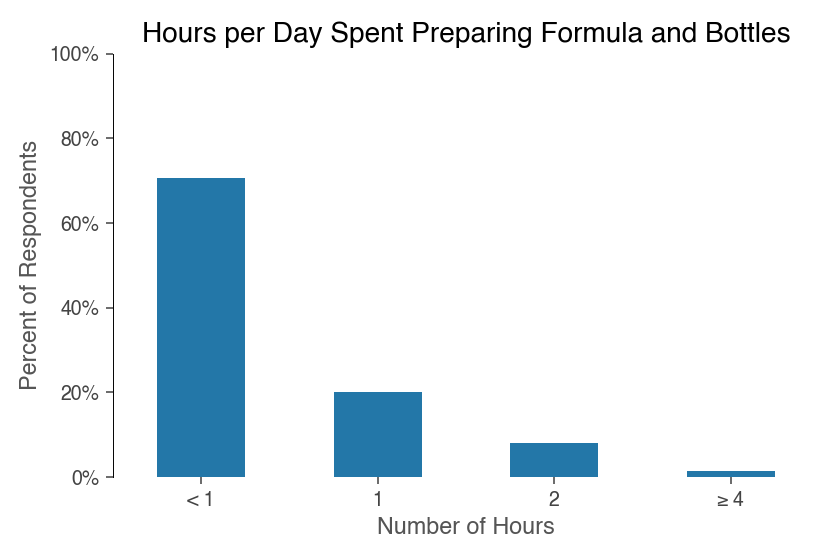

Feeding formula requires additional time to prepare formula and clean bottles. However, for most of those surveyed, this time was minimal:

Pumping

In addition to feeding the baby, many birthing mothers also have to spend additional time pumping breastmilk. Nearly the whole sample (110 out of 123 respondents) pumped at least in some capacity since the birth of their child.

Note that these pumping figures likely underestimate true pumping rates as this data was collected during social distancing. Many working mothers were able to breastfeed instead of pump while working from home.

While pumping allows for shared feeding responsibility, work outside of the home, and increased breastmilk supply, it is another burden on breastfeeding mothers. Pumping is additional labor and time being tethered to a pump (that you have to lug around and clean thoroughly).

“[Pumping is] so much extra time that isn’t spent with my baby. When I was nursing, then topping off with a bottle, then pumping during the short naps he took, I literally felt like all I did was feed him all day long.”

On average, mothers spent three hours pumping each day in the first two months of their babies’ lives. In months three and four, they pumped on average two and a half hours a day. Months five and six saw two hours of pumping, though again this figure may be depressed by social distancing.

“I wanted to cry when I would see a bottle of milk being poured down the drain because every 4 ounces represented a half hour of my time just being thrown away.“

To put this in terms of opportunity costs (again using our $18/hour wage example), the average respondent would have spent 180 hours pumping for an opportunity cost of $3240 in the first two months of their baby’s life. In the next four months, they would have spent an addition 270 hours pumping for another $4860 in pumping opportunity costs.

What are the physical and emotional costs of breastfeeding vs. formula?

Time and money are not the only costs to feeding a baby. There is often a physical and/or emotional toll paid by birthing mothers when feeding their child.

Regardless of what they fed their baby, the majority of respondents shared some kind of concerns or challenges faced with feeding.

Formula feeding parents mentioned “mom-guilt” and shared examples of how they faced shame or pressure from hospital staff for not exclusively breastfeeding their babies.

“‘Baby friendly hospital’ staff had strong opinions about formula use [and] made it seem shameful”

Others struggled to find the right formula for their baby (sensitivities or allergies to a formula can cause discomfort or medical concerns for a baby).

“No matter how many times I took her to [the doctor] I wasn’t listened to and just told that I needed to spend the time forcing her to take her bottles. It was like I was given a different baby when I finally found a doctor who believed me [..] and switched her formula.”

For those breastfeeding, many shared how painful the act of breastfeeding is:

“It was so painful in the beginning, I wish I had known to expect the pain.”

“[The] pain was never alleviated fully until we stopped nursing.“

“While I love it now, it was incredibly and unexpectedly painful and hard. I needed a lot of support from my husband, family, and [lactation consultants].”

After getting through the initial pain, breastfeeding moms deal with a second wave of pain when their babies get teeth:

“Further pain has been felt since there [are] now teeth to consider during breastfeeding”

Breastfeeding also encumbers mothers’ time away from their baby. Leaving their baby requires planning both to ensure the baby is fed and to deal with milk production while not nursing. In turn, some mothers experience an added loss of freedom with the breastfeeding experience:

“I feel tied to my baby, like I can’t go anywhere without him for more than a couple hours without careful advance preparation (pumping, washing pump parts, decanting into bottles, defrosting bottles, packing bottles, etc.).“

The majority of those breastfeeding also pumped, and generally did not have good things to say about the pumping experience. As one respondent aptly put it:

“[Pumping] f***ing sucks (literally and figuratively).”

Pumping can cause additional anxieties about planning, milk production, time spent attached to a machine, difficulty caring for baby while pumping, and overall lack of enjoyment.

“I NEVER feel comfortable pumping around others because I feel like a livestock animal hooked up to a dairying machine.”

“I found pumping to be very depressing for me and not something I would willingly do.”

Some mothers pump to increase their supply, or struggle with producing as much milk when pumping as they do when nursing. As such, a number of respondents reported feeling anxiety over their milk production when pumping:

“[Pumping] gave me so much stress because I thought I didn’t produce enough”

As these quotes illustrate, feeding a baby can take a toll on birthing parents emotional and/or physical wellbeing, regardless of whether you are breastfeeding vs. formula feeding.

How much are lactation consultations and feeding education?

Feeding a baby is also not as intuitive as it sounds – many families spend additional time and money on baby and breastfeeding classes, and lactation consultants.

When we were handed our baby for the first time, we have absolutely no idea how to feed him. We needed patient nurses and a lot of feeding charts to get the hang of it.

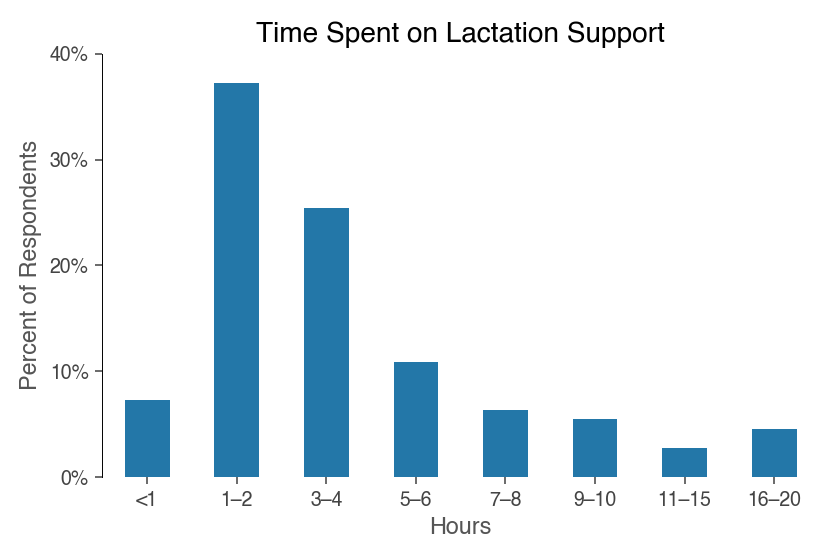

And we weren’t alone in this. A large majority of those surveyed (83% of the sample, n=102) reported spending at least an hour or more with a lactation consultant or on breastfeeding troubleshooting.

The majority of families needed four hours or less of breastfeeding troubleshooting support. On average, people spent about five hours working on their breastfeeding.

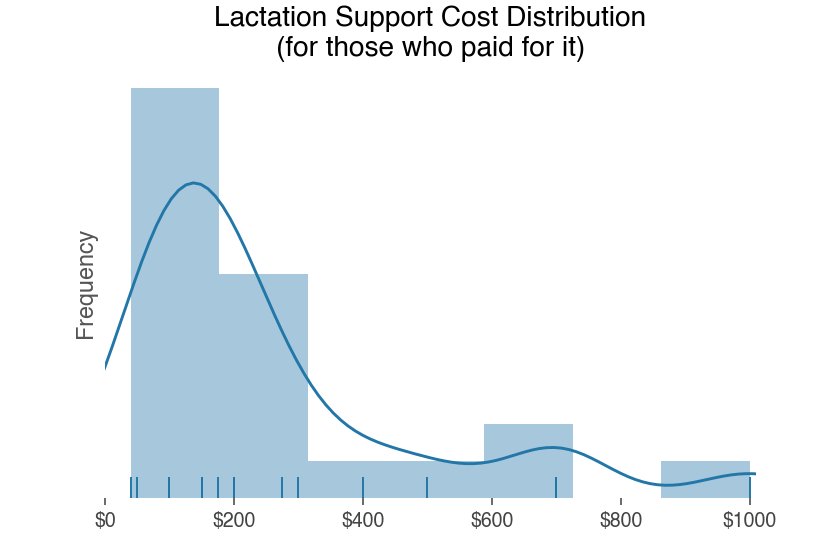

There was no cost associated with lactation support for 72% of those who used it (n=74). Those who had to pay incurred costs between $40-$1000, with an average expense of $265.

Some reported that they would have liked more lactation support but it was cost prohibitive.

“We probably could use more lactation consulting work, but we cannot afford it right now”

While feeding support is generally thought of as a breastfeeding concern, a few respondents commented on how they wished more education was available for formula feeding. For example:

“I really wish that the nurses and lactation consultant in the hospital had been more honest with me and given me more education about formula feeding. Everything I had been taught was so pro-breastfeeding that I was worried my baby would struggle on formula. Mix that in with postpartum hormones, and I was a mess.

I agree with these comments. Formula feeding isn’t as straight forward as it seems, and from our experience it has been hard to get clear answers to questions about feeding volumes and schedules. We’ve heard a lot of ‘it is different for every baby’ and ‘whatever works for you.’ Understandable, but leaves a lot of room to doubt whether about you are correctly feeding your kid.

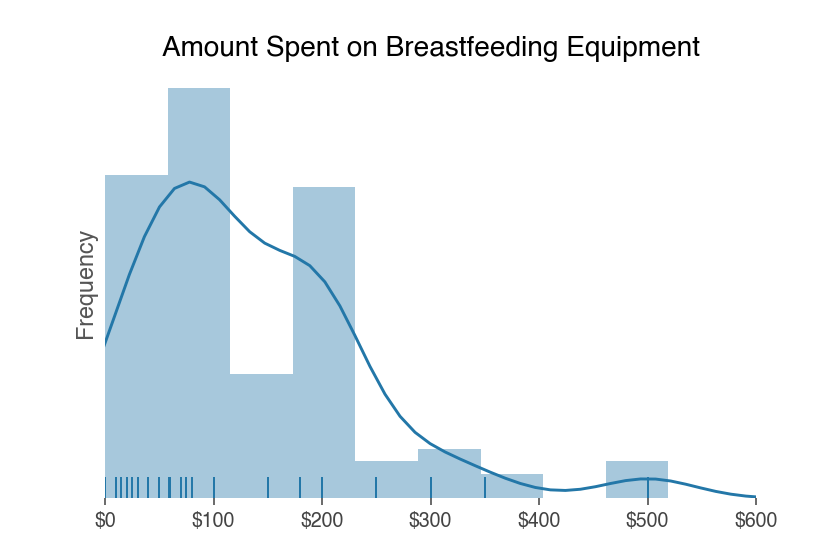

How much does breastfeeding vs. formula feeding equipment cost?

Now turning to the expenses you traditionally see in breastfeeding vs. formula feeding articles, how much does feeding gear and formula cost Given how much time is spent feeding a baby, having proper equipment often has good return on investment for new parents.

Below is a breakdown of example costs for gear for formula feedings vs. breastfeeding vs. pumping. Respondents also shared the expenses they incurred to feed their babies.

Note that respondent averages may slightly underestimate costs in each category, as some people used gear for multiple purposes. For example, an individual may have seen their bottle costs as a ‘pumping expense’ instead of a ‘formula expense,’ even if they used them for both purposes.

Formula Feeding

At a minimum, formula feeding a baby requires bottles and nipples. For those feeding formula regularly, there are accessories that make the job easier.

For our formula set up, we have: a lot of bottles in multiple sizes (to cut down on cleaning frequency), nipples with different flow levels, a formula mixing pitcher, a dishwasher basket for cleaning parts, a bottle parts drying tray, travel formula containers, bottle warmer, and a bottle brush (that we didn’t use much).

I got most of our formula feeding equipment used and free on Facebook, so I spent a total of $33.97 for our whole set up (see my monthly baby expense reports for more examples of how I save by getting baby gear through Facebook).

Buying new, you would end up purchasing the following:

- bottles: price varies by size and brand

- nipples: price varies by brand (TIP: If you start with ready-to-feed formula bottles at the hospital, hang on to the nipples to cut down on this expense).

- formula mixing pitcher: this makes mixing formula much easier

- dishwasher basket for bottle parts

- drying tray for bottle parts

- travel formula container: these are so useful any time you’re away from home

- bottle brush: we didn’t actually find this useful but you may depending on the bottle brand

- bottle warmer: an optional purchase but can be convenient for some babies.

Related Post: How to Clean a Dr. Brown’s Bottle Warmer

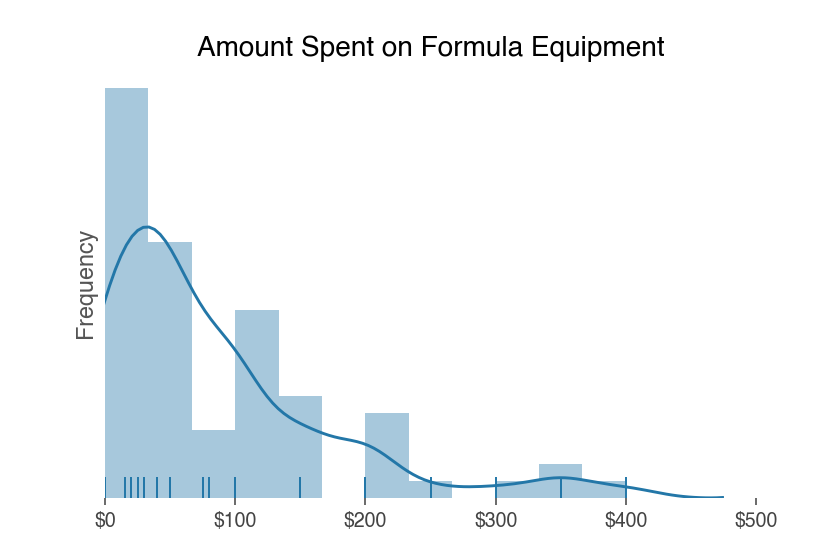

The 71 respondents who provided formula feeding costs spent an average of $85 on their formula gear.

Their costs ranged from $0 to $400.

Breastfeeding

Of the 111 respondents who breastfed from the breast, 108 shared their estimated expenses for breastfeeding accessories. Their expenses ranged from $0 to $1500.

On average, breastfeeding families spent $148 on breastfeeding gear.

These costs did not include lactation consultations or pumping costs (discussed above).

Example breastfeeding expenses include:

- nursing clothes: such as tanks, bras and dresses

- nursing pillows: boppy or brestfriend pillow

- mother’s breastfeeding related medical costs: varies with insurance (e.g. mastitis or chiropractic care)

- nipple creams

- nipple pads: reusable or disposable

- nipple shields

- hot/cold packs

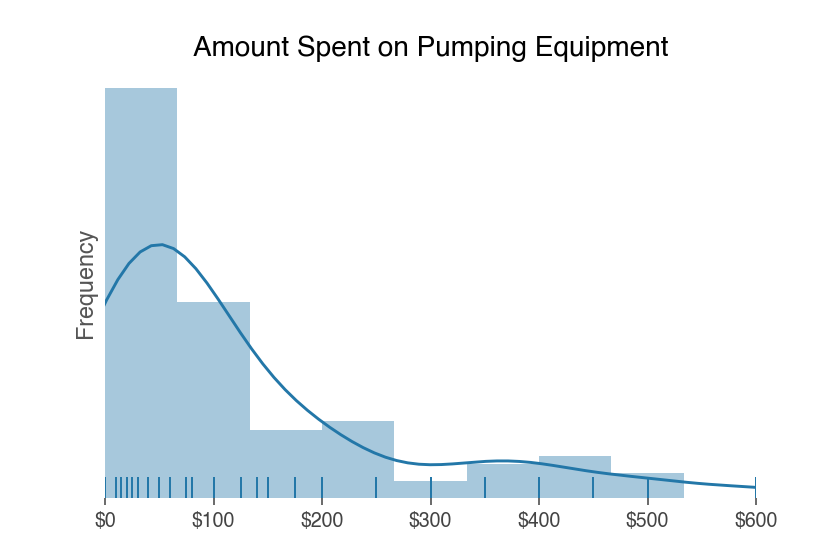

Pumping

One hundred and eight respondents shared their estimated pumping related expenses.

Pumping expenses could include the pump itself, replacement parts like tubing (replace kits ~$15-$30), breastmilk storage items like bags or bottles, nipples for baby bottles and pump friendly clothing.

“Spare parts and storage bags make up most of the cost [of pumping]”

On average, pumpers spent $148 dollars on pumping items. The amount spent ranged from $0 up to $100.

In the United States, breast pumps are covered by health insurance through the Affordable Care Act. That said, the quality of the pumps available vary across insurance plans.

Some people may end up purchasing a better or second pump (so as not haul a pump with them to work every day). Electric pumps range in price from about $50 to $200. Manual pumps are cheaper – like the much touted Haakaa, a suction pump used to collect letdown from the non-feeding breast.

Insurance provided pumps are usually not hands free. Truly hands pumps, like the Willow or the Elvie, are an investment. There are bras designed to make pumping hands-free, but they are another expense and don’t work for everyone.

“It would be nice to pump while working so that feeding the baby doesn’t eat into my billable work hours. However, there is no good way to pump hands-free unless you buy a very expensive pump that is not covered by insurance. I have an objectively “good” pump that was covered by my insurance, and pumping hands-free doesn’t really work. I spent $50 on two different pumping bras that are supposed to be “hands-free,” but neither is truly hands-free.“

Hands free is important though because it allows women to do other things, like their jobs, while pumping.

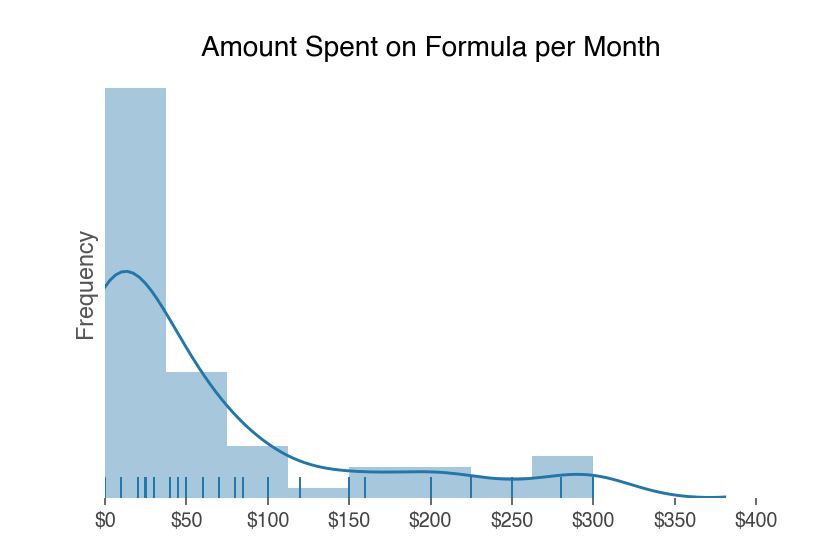

How much does formula cost?

Lastly, let’s take a look at formula costs. Formula feeders have the added expense of formula costs that breastfeeding families don’t incur.

The cost of formula varies widely based on: brand; gentle type (with partially hydrolyzed whey protein for easier digestion); allergy requirements; organic; and powdered vs. liquid types.

That said, formula samples are also readily available from formula companies and from pediatrician offices. Based on medical needs or socioeconomic situation, formula costs may also be subsidized by health insurance or government programs.

“We initially received enough free formula [..] that we did not have to spend money on formula until month four of life”

“[We] were able to use samples from the hospital and doctors office.”

Many survey respondents noted that they received enough free formula to not incur any formula expenses. Overall, seventy-four respondents who used at least some formula indicated that they had no monthly formula expenses.

We personally use Costco’s Kirkland brand formula, which is a standard powdered formula. Powdered formula is cheaper than ready-to-feed liquid formulas, and standard formulas run cheaper than gentle, hypoallergenic and organic formulas. We spend approximately ~$60/month on formula.

As a comparison, a month supply of name-brand formula like Similac costs ~$120-140 a month (price in March 2020). For a full run down of powdered formula cost comparisons, see the post: Is Costco Cheaper for Baby Items?

Ready-to-feed liquid formula is more expensive. Ready-to-feed formula can cost about 25 cents per oz. compared to Kirkland’s 6 cents per oz (prices as of March 2020).

We use [ready-to-feed formula]. This increases our costs but eases items like making formula and responsibility of feedings falling on one parent.

One respondent noted their monthly ready-to-feed formula costs to be about $300. As the quote above highlights, for them, this was a worthwhile tradeoff to lessen and more evenly distribute the work load. A respondent who needed hypoallergenic formula noted their costs to be about $250 a month.

“Buying a tin for baby not to like it sucks! He hasn’t liked any so far.“

Some respondents also reported lost costs in experimenting with different formula types.

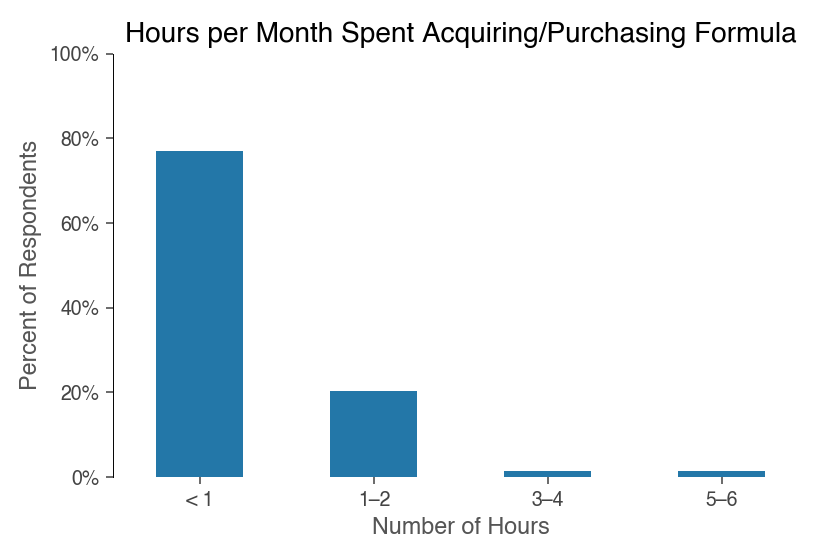

On average though, the respondents (n=70) who used formula reported a monthly cost of about $61. Time spent buying formula was minimal:

Totaling up breastfeeding vs. formula feeding time and costs

There are a lot of possible time commitments and costs to feeding your baby, regardless of whether you are breastfeeding vs. formula feeding. To conclude, what do these time and money costs look like when you total them all together for the first six months of life? And how do these totals compare across breastfeeding vs. formula feeding vs. combination feeding?

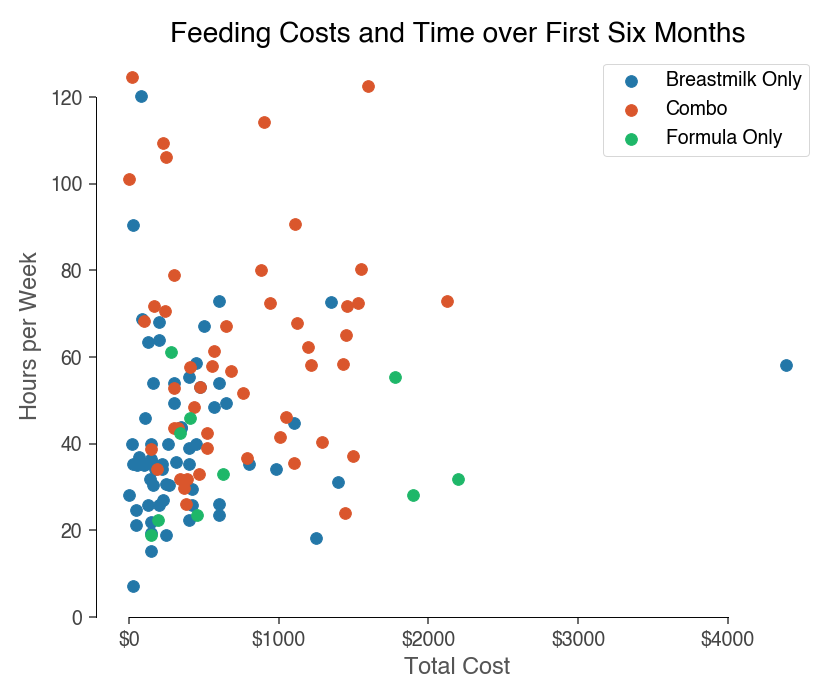

The graph below plots each respondents totaled time in all feeding related acts (i.e. feeding itself, pumping, acquiring milk or formula, cleaning equipment) by their totaled expenses (i.e. equipment, formula or donor milk costs, lactation consultant costs) when their babies were 0-6 months old. The data points are then color-coded by breastfeeding vs. formula feeding vs. combo feeding.

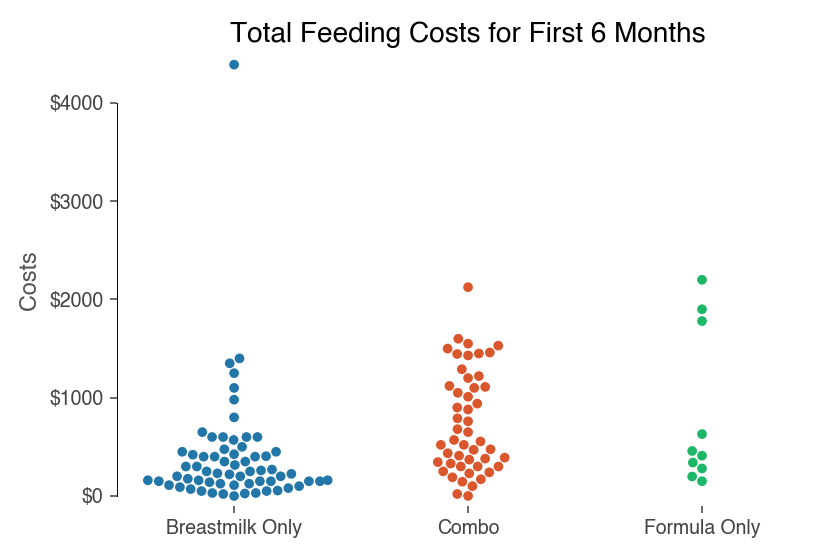

First, looking at money spent:

- Breastmilk only: families spent $402 on average

- Combination feeding: families spent $751 on average

- Formula only: families spent $835 on average

Since formula feeding families have regular formula expenses, it makes sense that their total costs would be the highest in the sample. Interestingly, the breastmilk-only group spent only a few hundred dollars less on feeding costs than the combination and formula feeding groups.

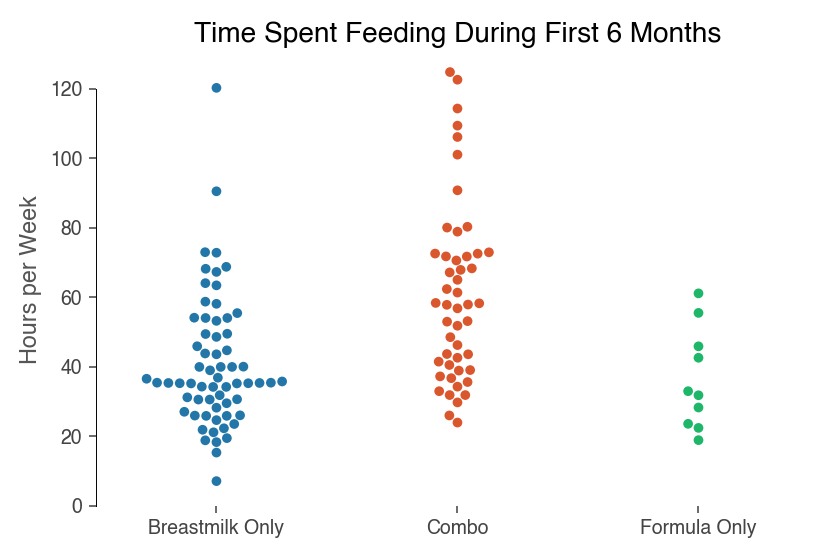

In terms of time:

- Breastmilk only: families spent an average of 41 hours per week

- Combination feeding: families spent an average of 61 hours per week

- Formula only: families spent an average of 36 hours per week

At first blush, these results are surprising. Combination feeding families were estimated to spend a lot more time feeding than their peers – 20+ hours a week more. It would make sense that their feeding times would be higher since they have to spend time on breastfeeding activities (like pumping) and formula activities (like preparing and cleaning bottles). However, the total still seems a bit on the high side.

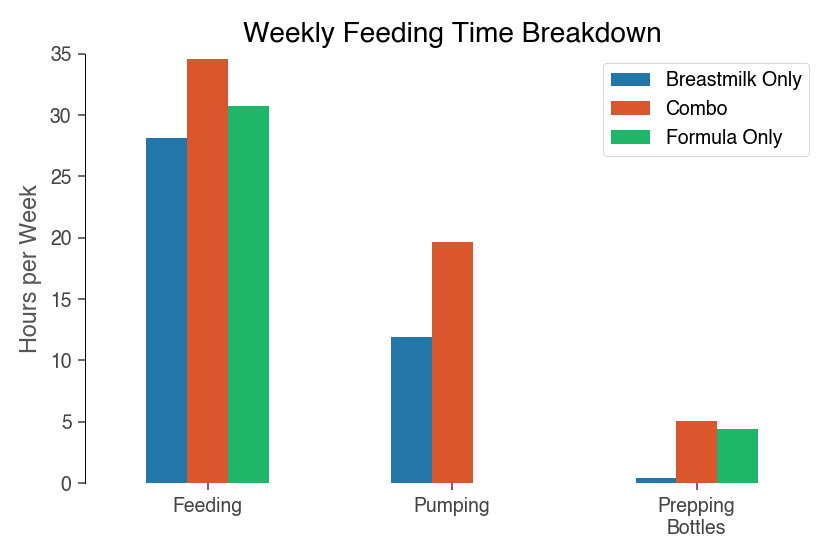

When you disaggregate the time spent across feeding activities, you see that combination feeder spend more time both in the actual feeding on their babies and in pumping than breastmilk-only respondents.

One possible theory for this increased time burden is that those who combination feed are a group who had a less efficient or harder breastfeeding experience, driving their decision to supplement or switch feeding methods.

This twenty hour difference for combination feeders totals to about 460 extra hours over six months. While breastfeeding was the cheapest in terms of costs, breastmilk families also spent 115 more hours in total feeding activities than formula families. Converting that 115 hours to opportunity costs yields about $2070 in earning potential at the average hourly wage.

Key takeaways

- If you had to pay women for their time spent feeding, it’d total over $14,000 for the first six months of a newborn’s life.

- You’re going to spend a lot of time feeding your baby, regardless of feeding method.

- Breastfeeding saves you about $400 compared to formula feeding in the first six months of life, but costs about an extra 115 hours and feedings are not easily shared with co-parents.

- After the first six months, formula feeders would continue to face recurrent formula expenses, whereas non-formula feeders likely paid most of their monetary expenses around birth (buying nursing clothes, lactation consultants etc.).

- Combination feeders incurred the highest time burden of all the feeding groups.

Let me know what you think about this article in the comments. I’d love to hear about your feeding experiences or answer any questions you have!

![Do You Really Need a Baby Bath Tub? [+ Alternatives]](https://shoestringbaby.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/do-you-need-a-baby-bath-300x300.png)